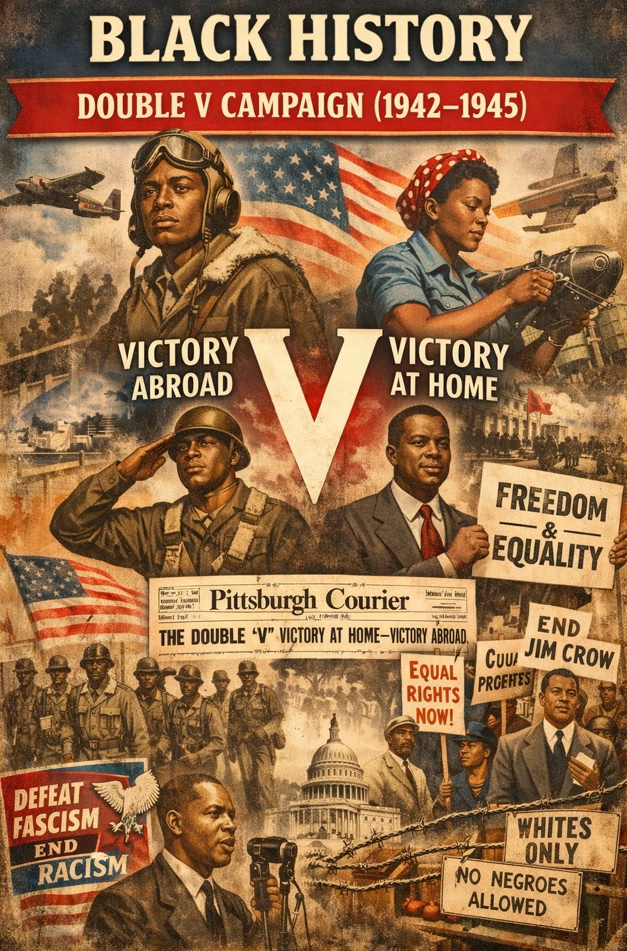

When “Victory” Meant Two Different Things

In the early 1940s, the word victory was everywhere. It rolled off radio broadcasts. It filled front pages. It hung in factory windows on bright posters marked with a bold V.

America was fighting fascism. That part was clear.

What felt less clear, at least for Black Americans, was where they fit inside that promise of freedom.

How do you fight for democracy overseas while being locked out of it at home? How do you train to defeat racial supremacy abroad while living under segregation in your own country?

Those weren’t abstract questions debated in think tanks. They were lived realities. Black men boarded trains to basic training in segregated units. Black women stepped into defense jobs long denied to them, only to face hostility on the factory floor. Families bought war bonds and rationed meat and sugar, yet still confronted poll taxes and discriminatory housing practices.

So when the phrase “Double V” emerged—Victory abroad and Victory at home—it resonated immediately. It gave language to a tension people were already carrying.

It wasn’t anti-American. It was deeply American. It simply insisted that the country live up to its own creed.

A Letter That Lit a Fuse

James G. Thompson, “Should I Sacrifice To Live ‘Half-American’”, The Pittsburgh Courier, January 31, 1942, newspapers.com.

The Double V Campaign did not begin with a march. It began with a letter.

In January 1942, James G. Thompson, a young Black man from Wichita, Kansas, wrote to the Pittsburgh Courier. He asked a direct question: why should he give his life defending a democracy that treated him as second-class?

There was no theatrics in his tone. Just clarity.

The Courier, one of the most widely read Black newspapers in the country, published the letter. Then it built on it. Editors turned Thompson’s idea into a formal campaign. Two V’s: simple, symmetrical, impossible to miss.

The power of the Black press during this era cannot be overstated. Newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Baltimore Afro-American were more than media outlets. They were connective tissue. They carried news across state lines, across regions, across generations.

When the Double V Campaign appeared in their pages, it traveled fast.

People wore Double V buttons on their lapels. Churches discussed it in Sunday sermons. College students debated it after class. It became shorthand for something larger: we will fight for this country, and we expect this country to fight for us.

Serving a Nation That Segregated You

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

By the end of World War II, more than one million Black men had served in the U.S. military. They trained hard. They deployed overseas. They faced enemy fire.

But they did so in segregated units.

Black service members were often assigned to labor battalions, supply units, and support roles. Leadership positions were limited. White officers typically commanded Black troops. The structure reflected long-standing racial assumptions.

And yet, performance told a different story.

The Tuskegee Airmen, trained in Alabama under intense scrutiny, became one of the most respected fighter pilot groups of the war. Their escort missions over Europe earned praise and quietly dismantled myths about capability. They didn’t argue their worth. They demonstrated it.

Black nurses served as well, though the Army Nurse Corps initially imposed strict limits on how many could join. Those who were accepted worked in demanding conditions, often assigned to segregated wards. They treated wounded soldiers with professionalism that never made national headlines.

There were countless others like mechanics, medics, drivers, and cooks whose names rarely appear in textbooks. But their labor sustained the war effort. Without them, the machinery of war would have stalled.

Still, when many returned home in uniform, they faced the same “Whites Only” signs. Some were attacked for wearing the very uniform that symbolized national defense.

That contradiction lingered.

Factories, Migration, and Federal Pressure

The battlefield wasn’t only overseas. It was also inside American factories.

World War II sparked massive industrial expansion. Aircraft plants in California. Shipyards in Michigan. Steel mills in Pennsylvania. The demand for labor surged, and hundreds of thousands of Black Americans left the rural South for industrial cities in what historians call the Second Great Migration.

The move promised opportunity. Better wages. A chance at something different.

But access to defense jobs was uneven. Many companies resisted hiring Black workers for skilled roles. Labor unions sometimes excluded them outright. Tensions escalated, and in cities like Detroit, racial violence erupted in 1943.

Pressure mounted.

Philip Randolph, a seasoned labor organizer and head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, threatened a massive March on Washington in 1941. His message was clear: if the federal government would not address discrimination in defense industries, Black Americans would make their grievances visible on the national stage.

The Roosevelt administration responded with Executive Order 8802. It prohibited racial discrimination in defense industries and established the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC).

The order did not end discrimination overnight. Enforcement was inconsistent. Some employers complied only when pressured.

But the precedent mattered.

For the first time in decades, the federal government acknowledged that employment discrimination was not merely a local issue. It was a national concern.

That shift would echo long after the war ended.

Suspicion, Backlash, and Strain

Not everyone embraced the Double V message.

Some white Americans viewed the campaign as divisive. Federal agencies monitored certain civil rights leaders, concerned that organized protest might disrupt wartime unity. Advocating for equal rights during a global conflict required careful language.

Black leaders had to walk a narrow path, affirming commitment to the war while challenging inequality at home.

On factory floors, resentment sometimes boiled over. White workers protested integration. In some cases, they staged walkouts rather than share space with newly hired Black employees. The FEPC investigated complaints, but it lacked strong enforcement power.

Progress came in increments.

And the emotional toll was real.

Black soldiers overseas read about racial unrest in American cities. Families back home balanced pride in service with anxiety about discrimination. Fighting two battles at once—one abroad, one domestic—required stamina.

Community institutions became anchors. Churches, civic clubs, and Black-owned businesses offered not just strategy but support. The Double V symbol carried hope, but also responsibility.

It was heavy at times.

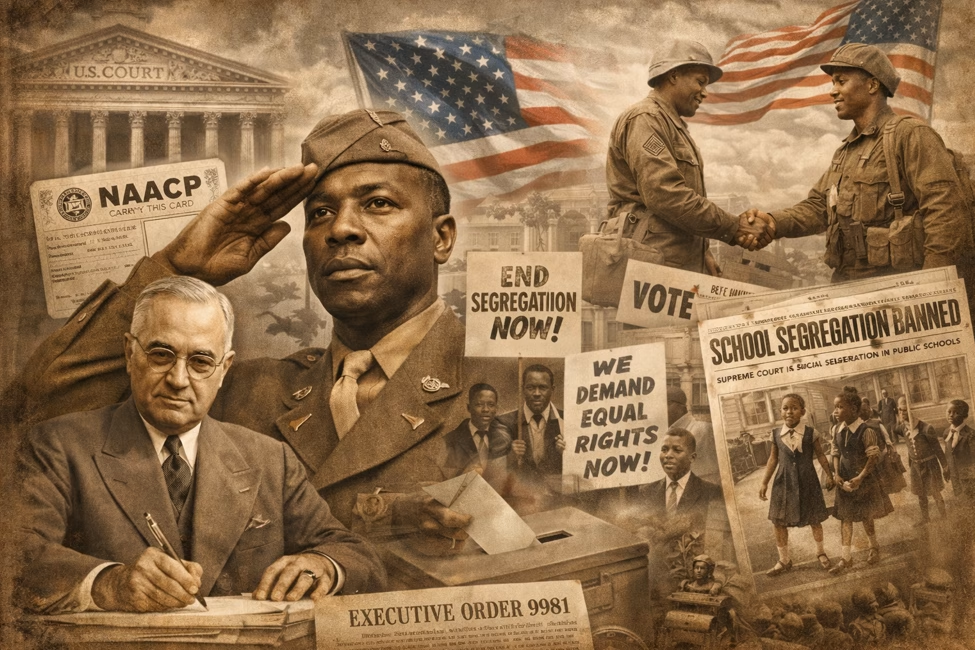

The Bridge to the Civil Rights Era

When World War II ended in 1945, segregation laws remained in place. Voting barriers persisted. Housing discrimination continued.

Yet something fundamental had changed.

Black veterans returned home less willing to accept second-class status. Organizations like the NAACP saw membership grow significantly during and after the war. Legal challenges intensified. Courtrooms became new battlegrounds.

The logic of Double V that democracy must be consistent, appeared in legal arguments that eventually led to Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. The idea that segregation contradicted constitutional principles was not new, but wartime activism had amplified it.

In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, desegregating the armed forces. That decision reflected years of pressure and the undeniable reality that Black soldiers had served with distinction.

Double V did not resolve every injustice. But it built infrastructure. It expanded expectations. It made federal intervention in civil rights matters more plausible.

Those gains were partial. They were contested. Still, they mattered.

A Framework That Endures

The Double V Campaign offers more than a historical footnote. It offers a framework.

It shows that patriotism and protest are not opposites. It demonstrates that organized pressure through media, legal advocacy, and public mobilization can influence national policy. It underscores the connection between how a nation presents itself abroad and how it treats its citizens at home.

There were limits. Many wartime reforms were narrow. Economic gaps remained wide. Violence and discrimination did not disappear.

But the campaign reshaped the conversation.

It asserted that freedom cannot be compartmentalized. That democracy must function on every front. That service deserves dignity.

Two V’s once printed on buttons carried that message. The symbol may feel distant now, but the principle remains familiar.

Victory is not only about defeating an external enemy. It is also about confronting internal contradictions.

And that work, demanding that America become what it claims to be, continues.