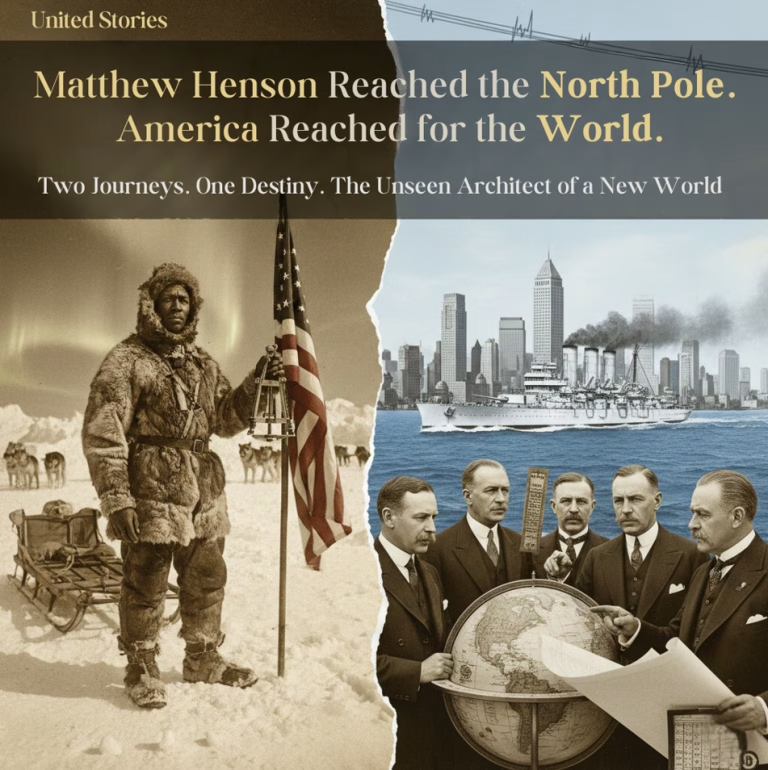

April 6, 1909. Imagine a world of crystalline silence, shattered only by the rhythmic crunch of iron-shod sleds against the unforgiving pack ice of the High Arctic. At the literal apex of the world, a man stands amidst a maelstrom of spindrift and absolute zero. He is not the face history books first chose to remember, yet he is the one who held the sextant. Matthew Henson—a polymath of survival and master of Inuit linguistics—plants the Stars and Stripes into the North Pole. In that frozen moment, the cartographic terra incognita of the nineteenth century vanished.

But this wasn’t merely a trophy for the American ego. The conquest of the Pole was the quintessence of a burgeoning national teleology. As Henson’s leaden footsteps marked the 90th degree latitude, the United States was shedding its chrysalis of continental isolationism. The same year Henson conquered the ice, the U.S. was finalizing its ascent as a global hegemon, transitioning from a nation obsessed with its own borders to an empire with an insatiable appetite for the horizon.

The Strenuous Life and the New Frontiers of 1898

The turn of the century birthed a feral, expansionist ethos known as the “strenuous life.” At the vanguard stood Theodore Roosevelt, whose “big stick” diplomacy was as much a psychological doctrine as a military one. Roosevelt championed the idea that American virility was maintained through struggle. While the political establishment viewed the world through the lens of imperial duty, Matthew Henson embodied the extreme of this grit, navigating the sub-zero crucible of the North while the nation debated the spoils of warmer climates.

This era marked a transition from Manifest Destiny to Global Destiny. By 1890, the Census Bureau declared the American frontier closed. The solution was an outward-looking posture, shifting focus from the dusty plains to the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the Arctic. The 1898 catalyst—the Spanish-American War—transformed the U.S. into an overseas sovereign, managing disparate populations across vast longitudinal gaps. As the U.S. Navy began to patrol new global holdings, the quest for the North Pole became the ultimate symbolic capstone of this expansion.

Precision and Power: The Technical Architecture of Globalism

The dawn of the twentieth century was obsessed with the eradication of “slack.” In Philadelphia and Detroit, Frederick Winslow Taylor was codifying scientific management, the pursuit of the “one best way” to perform any task. While corporations like Ford and Standard Oil were breaking down labor into timed components, Henson was applying a parallel rigor to the most unstable environment on Earth. Henson was the living embodiment of the “Henson Standard”: a level of technical fluency so absolute that Robert Peary admitted he was functionally helpless without him. In an era where mainstream institutions claimed a monopoly on scientific achievement, a Black navigator held the master key to the Pole’s lethal geometry.

This obsession with engineering found expression in the simultaneous pursuit of the Panama Canal and the North Pole. Both were frantic attempts to “shortcut” the globe. While Henson redesigned sled runners to minimize friction, American steam shovels carved through the Continental Divide. The canal was the industrial equivalent of Henson’s navigational lines, a move to compress the distance between power centers.

The Diplomatic Compass: From Isolation to the World’s Policeman

By 1917, the strategic muscle memory developed during Arctic expeditions was ready for its baptism in fire. The navigational daring Henson displayed, calculating solar altitudes without landmarks, became the foundational grit of the American officer class during World War I. The Atlantic was no longer a barrier; it was a highway.

This era witnessed the birth of Wilsonian idealism, arguing that American interests were linked to the universal spread of democracy. This political evolution mirrored the conquest of the Pole; both required the hubris to believe that American values could thrive in any climate. With the Pole claimed, the “Global Grid” was finalized. The world map was no longer a collection of disjointed territories but a singular, manageable board. This allowed leadership to treat international relations with the same mathematical precision Henson used to track his position amidst the ice.

The Shadow of Jim Crow in a Global Spotlight

The ascent of empire was marred by a jarring paradox. While projecting “freedom” abroad, the nation codified a domestic caste system. In 1896, the Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision sanctioned “separate but equal,” effectively ossifying Jim Crow. The United States was bifurcating its soul: reaching for the stars while tightening the shackles of segregation.

Matthew Henson stood as the unrecognized blueprint of this era’s success. Mainstream history painted globalism as a triumph of Anglo-Saxon ingenuity, necessitating the erasure of Black brilliance. Henson was the primary navigator and the only member who could communicate with the Inuit—the people whose survival technology made the journey possible. Yet, the establishment relegated Henson to a “valet,” claiming the Pole as a victory for a segregated society.

However, this globalism inadvertently sowed the seeds of the “Double V” campaign—Victory abroad and Victory at home. By placing American ideals on a world stage, architects invited international scrutiny. The contrast between inclusive teamwork on the ice and the stifling atmosphere of the South created an unsustainable friction. The reach of empire expanded the horizons of the oppressed, turning a domestic fight into an international crusade for human rights.

Legacy of the 1909 Milestone: A Blueprint for the Modern World

The 1909 expedition was the prologue to a new geostrategic orthodoxy. During the Cold War, the North Pole transformed into a theater of asymmetric vigilance. The Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line and nuclear submarines mirrored the routes Henson had navigated by dog sled.

Tracing the lineage of power reveals that the explorers of the 1900s were the harbingers of the 1940s economic architects. The impulse to plant a flag at the Pole eventually led to the Bretton Woods Conference and the birth of the IMF and United Nations. These institutions managed a world rendered “small” by men like Henson, a world where the American dollar and diplomacy could reach the most remote latitudes like a polar wind.

Henson’s legacy has undergone a necessary correction. For decades, a world-class navigator worked as a clerk, yet his “quiet victory” lay in the proof of his competence. Today, we recognize that diversity is a prerequisite for global leadership. The blueprint for the modern world, initially drafted in 1909, now acknowledges that the American Century was built by those who stood at the sextant in the dark.

Recalibrating American Greatness

American globalism was a gritty syncretism of Black grit and White ambition. While gatekeepers framed the Pole as a monolithic achievement, the reality was a partnership of necessity. Henson provided the vernacular intelligence and technical precision that transformed Peary’s grandiosity into victory. We must dismantle the myth of the “lone genius” and recognize the collaborative force that built the American Century.

The planting of the flag at the 90th degree was the psychological bridge to an interventionist future. The Arctic triumph proved that the American reach was no longer bound by temperate zones. As we look back, we must seek the “unseen navigators” hidden in the official record. History is often written by those who held the pen, but it is made by those who held the sextant in the dark.

Whether in the engine rooms of the first steamships or the labs of the Space Race, there is always a Matthew Henson, a figure of superlative skill whose contributions were the “silent fuel” for the nation’s ascent. Do not settle for sanitized narratives. By acknowledging the diverse hands that mapped our world, we gain a more sophisticated compass for our future. To understand where we are going as a global power, we must first tell the full truth about how we got here.