Introduction

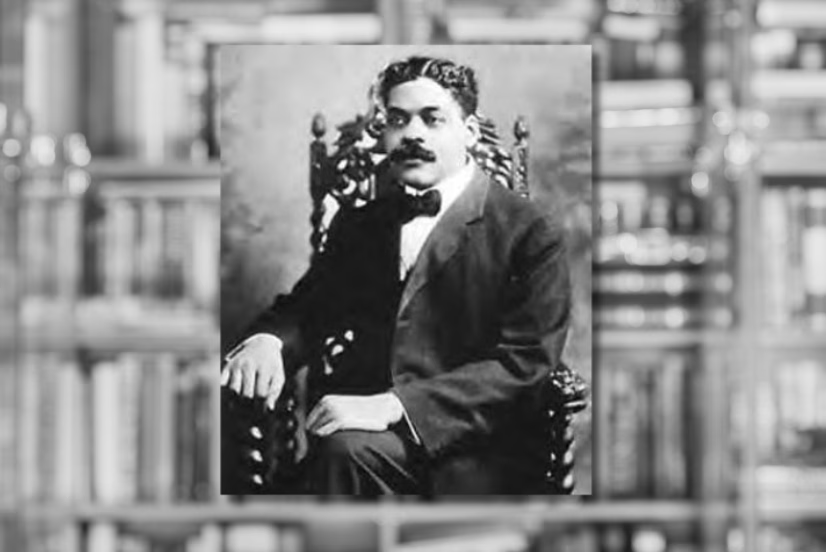

In the annals of African American history, one name rises above the rest when it comes to uncovering the hidden truths of the Black experience: Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874–1938). Known as the Black Sherlock Holmes, Schomburg was a Puerto Rican-born historian, bibliophile, and activist who made it his life’s mission to uncover, collect, and preserve the history of people of African descent. His tireless efforts challenged centuries of erasure and gave birth to one of the most important archives of Black culture in the world—the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem, New York.

But how did a young boy born in Puerto Rico, once told by a teacher that “Black people have no history,” become the man who proved otherwise? His journey from student to detective of forgotten histories is one of resilience, passion, and intellectual brilliance.

Early Life and the Spark of Curiosity

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg was born on January 24, 1874, in Santurce, Puerto Rico, to a Black mother of St. Croix descent and a father of German heritage. His mixed-race background gave him a unique perspective on identity and race.

As a young student, Schomburg once asked about Black contributions to world history. His teacher dismissed him, saying bluntly: “Black people have no history, no heroes, no achievements.” This moment seared itself into his memory. Instead of discouraging him, it sparked a fire. Schomburg vowed to spend his life proving his teacher wrong. He would show the world that people of African descent had shaped civilizations, science, politics, art, and literature for centuries.

In 1891, at age 17, Schomburg migrated to New York City. He arrived in a world where Black people faced deep racial prejudice but also where vibrant communities of Caribbean immigrants and African Americans were building the foundation for what would become the Harlem Renaissance.

Schomburg found work as a printer, elevator operator, and messenger, but his true passion lay in study and research. By night, he poured over books, scoured libraries, and began collecting rare manuscripts and artifacts related to the African diaspora.

He became involved with political and intellectual groups, including the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico and the Cuban War for Independence movements. These connections broadened his understanding of global struggles for freedom and strengthened his belief that history itself was a tool for liberation.

The Detective of Black History

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, circa early 1900s. Credit: NAACP Des Moines

Schomburg earned the nickname the Black Sherlock Holmes because of his uncanny ability to track down rare documents, overlooked manuscripts, and forgotten stories. Just like the fictional detective solved mysteries, Schomburg solved the riddle of erased Black history.

His research uncovered long-ignored truths:

- He found records of Juan Garrido, an African conquistador who came to the Americas with Hernán Cortés in the early 1500s.

- He highlighted the life of Benjamin Banneker, the self-taught African American mathematician and astronomer who helped survey Washington, D.C.

- He exposed the legacy of Phillis Wheatley, the first published African American poet.

- He collected works of Haitian revolutionaries, African royalty, and writings that revealed the deep intellectual traditions of the Black world.

Each discovery was like a piece of a puzzle, building a larger narrative of achievement and dignity that contradicted the racist assumptions of his time.

Building a World-Class Collection

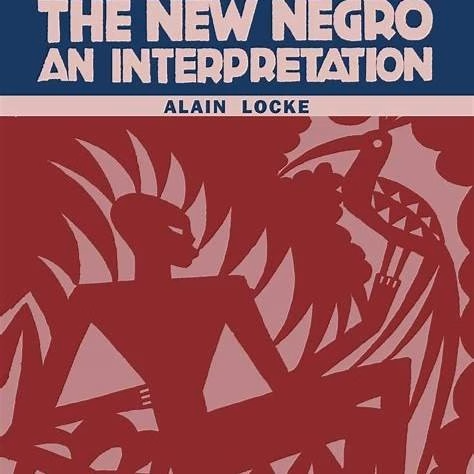

Cover of Alain Locke’s The New Negro — the landmark 1925 anthology that featured Schomburg’s essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past.” (Representative cover image.)

By the early 20th century, Schomburg had amassed one of the largest private collections of books, manuscripts, and artifacts about Black history. His apartment in Harlem was stacked floor-to-ceiling with treasures: rare slave narratives, African artwork, early Black newspapers, and even personal letters of famous leaders.

His collection attracted attention from scholars, activists, and educators. He often opened his doors to young Black students, encouraging them to learn about their heritage. His belief was simple yet powerful: history is ammunition for freedom. If Black people knew their true history, they would never accept the lie of inferiority.

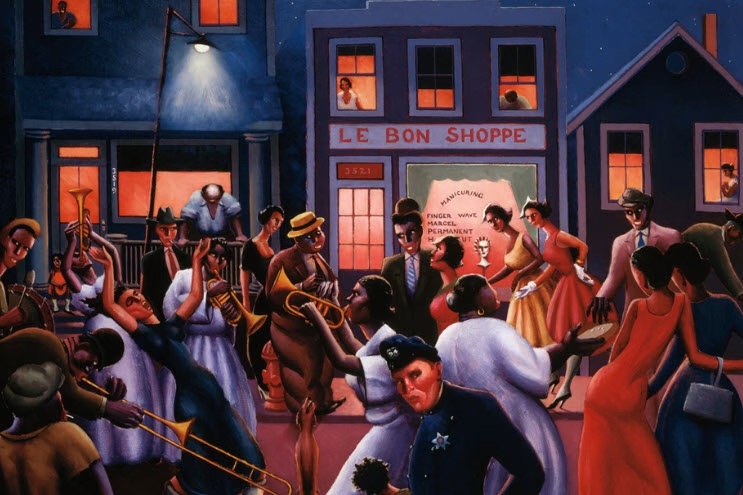

Harlem Renaissance and Influence

Schomburg’s work aligned perfectly with the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, a cultural explosion of Black art, music, and literature. Writers like Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Claude McKay drew inspiration from his discoveries.

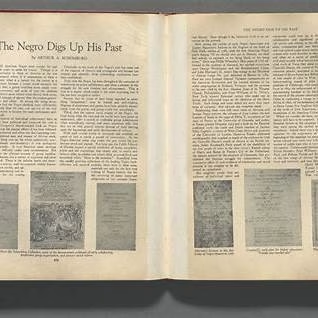

In 1925, his essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past” was published in Alain Locke’s anthology The New Negro. In it, Schomburg declared:

“The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future.”

This statement became a rallying cry for the Renaissance. His role as an elder statesman of history cemented his reputation as one of the movement’s guiding intellectuals.

The Schomburg Collection Becomes a Legacy

Spread of Arturo Schomburg’s essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” first published in The New Negro (1925). Courtesy of NYPL exhibition site.

In 1926, the New York Public Library purchased Schomburg’s massive collection for $10,000—a significant sum at the time. He was hired as curator of the newly named Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints at the 135th Street Branch Library in Harlem.

This institution would later become the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, now one of the world’s leading repositories of Black history and culture. Thanks to Schomburg, millions of people today have access to rare documents, photographs, and recordings that might otherwise have been lost forever.

Personal Life and Character

Despite his reputation as a scholar, Schomburg remained humble. Friends described him as warm, approachable, and generous with his knowledge. He was a family man, raising three sons, and he remained deeply connected to his Puerto Rican and Caribbean roots.

Though not formally trained as a historian, his meticulous detective work earned him honorary recognition from academic circles. His ability to move between intellectual salons, grassroots gatherings, and political circles made him a bridge between communities.

Later Years and Passing

Schomburg continued to curate and lecture until his death in 1938. Even in his final years, he worked tirelessly to expand the collection and ensure the preservation of Black heritage.

When he passed away, he left behind not only an extraordinary collection but also a legacy of intellectual empowerment. He had turned the insult of a schoolteacher into a lifelong mission that changed how the world views Black history.

Legacy and Relevance Today

Today, the Schomburg Center in Harlem stands as a monument to his vision. Researchers from around the globe visit its archives. His story reminds us of the importance of representation in history—and the dangers of erasure.

Arturo Schomburg’s life proves that the past is never lost; it can be rediscovered, pieced together, and used as a foundation for pride and progress. He demonstrated that Black history is not a side note—it is central to the story of humanity.

Conclusion

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, the Black Sherlock Holmes, dedicated his life to proving a single point: Black people have a history, rich and deep, filled with triumphs, creativity, and resilience. He chased forgotten manuscripts like a detective chasing clues, and in the process, gave future generations the gift of knowledge.

In a world that often tried to erase Black contributions, Schomburg left behind a legacy that still speaks powerfully: to know your history is to know your worth.