When people talk about the rise of American power, they usually jump to World War II. Or the Cold War. Or the moment when the United States stood alone after the Berlin Wall fell.

But long before that, before Normandy, before Hiroshima, before NATO, there was Theodore Roosevelt.

Understanding Roosevelt is not about memorizing dates. It’s about tracing how a republic that once feared standing armies became comfortable sending fleets across oceans. It’s about asking a deeper question: how did America move from survival to dominance?

For Black Americans, that question carries weight. Because as the nation expanded outward, it was still struggling inward, wrestling with segregation, disenfranchisement, and racial violence. Global power and domestic inequality grew side by side. That contradiction is part of the story. We cannot separate them.

Roosevelt did not invent American ambition. But he systematized it. He gave it muscle.

And in doing so, he mapped the early architecture of the American superpower.

A Nation Outgrows Its Borders

By 1890, the American frontier was declared closed. No more “empty” land. No more westward release valve. The continental project was complete.

But the factories were just getting started.

Steel production soared. Railroads webbed the nation together like arteries. Oil fueled cities. Entrepreneurs built companies that operated at a scale that would have stunned earlier generations. The United States had become an industrial heavyweight almost overnight.

Here’s the tension: industrial capacity without global access creates pressure. Too many goods. Too much capital. Not enough markets.

That pressure pushes outward.

European empires were already carving up Africa and Asia. Britain ruled the seas. France managed colonies across continents. Germany was flexing new industrial strength. If America stayed inward-looking, it risked falling behind economically and strategically.

So the map changed, not because Americans suddenly wanted empire, but because power has momentum. And momentum rarely stops at borders.

The Rough Rider’s Creed: Strength as Policy

Theodore Roosevelt believed in effort. In exertion. In what he called “the strenuous life.”

To him, nations, like individuals, either rose through disciplined action or declined through comfort. It sounds almost like a motivational speech. But it was foreign policy.

Roosevelt absorbed the ideas of naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, who argued that sea power determined global influence. Control the oceans, and you influence trade. Influence trade, and you influence politics.

Simple. Strategic. Effective.

As Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Roosevelt pushed for modernization. More ships. Better ships. Trained officers. Industrial coordination between shipyards and steel manufacturers. He treated naval capacity like a corporate growth plan: identify gaps, invest resources, scale operations.

Then came the Spanish-American War in 1898.

The conflict was brief but decisive. Spain lost control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Roosevelt, who resigned to fight with the Rough Riders, returned home a national hero. The war altered America’s posture permanently.

The United States now possessed overseas territories. That was new. And controversial.

A country born from rebellion was now governing distant peoples.

That paradox would linger.

The Caribbean as Testing Ground

Roosevelt did not hesitate. In 1904, he introduced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. It declared that the United States could intervene in Latin American nations if instability invited European involvement.

In plain terms: America would police its hemisphere.

Some called it protection. Others called it imperial overreach. Both views have merit.

Consider the Dominican Republic. Facing debt and possible European intervention, it allowed the U.S. to manage its customs revenues. Washington collected tariffs and paid creditors directly. No formal colonization. Yet influence was undeniable.

Then there was Panama.

When Colombia resisted canal negotiations, Panamanian revolutionaries declared independence with quiet American naval support nearby. Soon after, the U.S. secured rights to build the Panama Canal.

The canal changed everything. Ships no longer needed to circle South America. Naval mobility increased dramatically. During both World Wars, it proved essential.

It was engineering. It was strategy. It was leverage.

And it cemented the idea that American power could reshape geography itself.

Across the Pacific: The Philippines and China

If the Caribbean was regional consolidation, the Pacific was global projection.

The Philippines presented a moral and military challenge. Filipino revolutionaries had fought Spain expecting independence. Instead, they faced American rule. The Philippine-American War followed: bloody and difficult.

The United States justified its presence as civilizing stewardship. Critics saw betrayal.

It was a harsh lesson. Democracy and dominance do not sit easily together.

Yet strategically, the Philippines provided a foothold in Asia. That mattered. China’s markets were vast, and European powers were carving out exclusive trade zones. The American “Open Door Policy” insisted on equal access rather than territorial division.

It was economic pragmatism wrapped in diplomatic language.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt sent the Great White Fleet on a global tour. Sixteen battleships circled the world. It was part deterrence, part theater.

If you’ve ever sat in a boardroom where presence alone shifts the conversation, you understand the move. Sometimes visibility is strategy.

Japan noticed. Europe noticed. The message was clear: the United States had arrived.

Diplomacy with Teeth

Roosevelt was not reckless. He preferred balance over chaos.

When Russia and Japan went to war in 1904, Roosevelt mediated peace negotiations in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The treaty ended the conflict and preserved equilibrium in East Asia. He earned the Nobel Peace Prize.

But this was not sentimental pacifism. It was calculated stability.

Negotiation works best when backed by credible strength. Roosevelt knew that. The fleet, the canal, the industrial base—they made American mediation persuasive.

Power, then diplomacy.

Not the other way around.

That model, project strength, broker peace, protect trade, became standard practice in the twentieth century.

Power at Home: The Often-Ignored Foundation

Here’s where the story complicates.

While expanding abroad, Roosevelt also pursued progressive reforms at home. He challenged monopolies. Regulated railroads. Protected consumers. Preserved natural resources.

Why does that matter for foreign policy?

Because global credibility depends on domestic cohesion. A fractured nation cannot sustain long-term influence.

Roosevelt believed that unchecked corporate power threatened stability. Breaking up trusts was not anti-business; it was nation-preserving. A stable economy supports military readiness. Regulatory authority strengthens executive leadership.

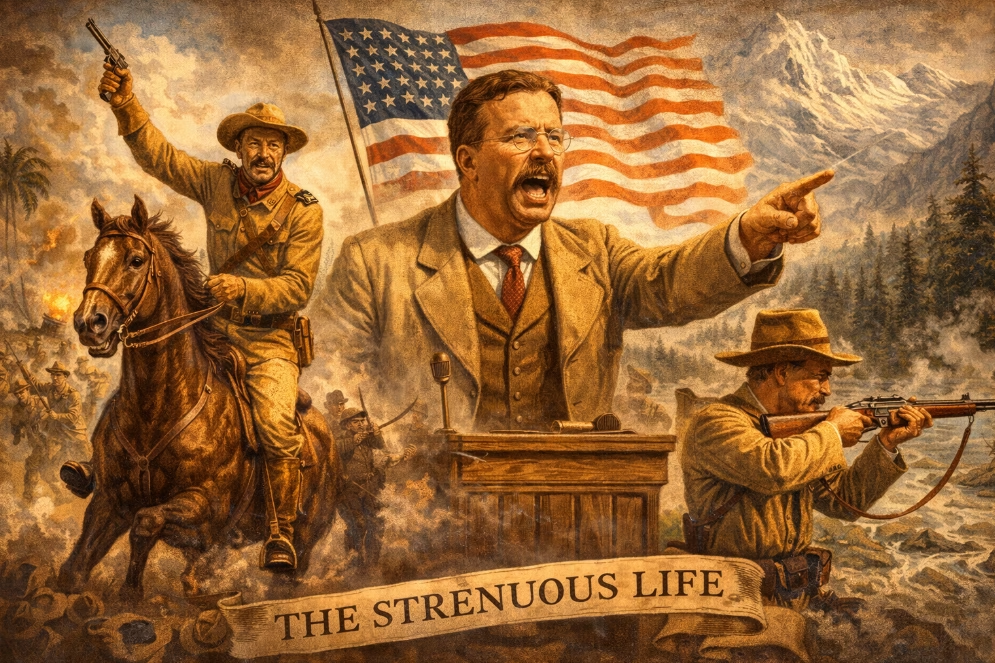

Still, Black Americans at the time experienced little of this progressive promise. Segregation remained entrenched. Voting rights were suppressed across the South. Roosevelt famously invited Booker T. Washington to the White House, an unprecedented gesture, but he did little to dismantle systemic racism.

That contradiction sits at the center of America’s rise: global democracy abroad, incomplete democracy at home.

It’s uncomfortable. But it’s real.

Redefining the Presidency

Roosevelt expanded executive authority in foreign affairs. He argued that the president could act unless explicitly forbidden by law.

That interpretation endured.

Woodrow Wilson would lead the nation into World War I. Franklin Roosevelt would guide it through World War II. Later presidents would manage Cold War alliances and interventions under similar assumptions of executive initiative.

Roosevelt helped normalize that concentration of power.

And once normalized, it rarely shrinks.

The Moral Question That Never Left

Was America building an empire—or assuming responsibility?

The Anti-Imperialist League said empire betrayed the Constitution. Others argued that global engagement was necessary for economic survival and strategic safety.

Both arguments echo today.

The United States emerged in the twentieth century not as a traditional colonial empire like Britain, but as something more diffuse, an influence network built on bases, trade agreements, naval mobility, and diplomatic leverage.

An imperium without constant annexation.

A superpower without formal crown colonies.

But influence, even informal, still shapes lives beyond borders.

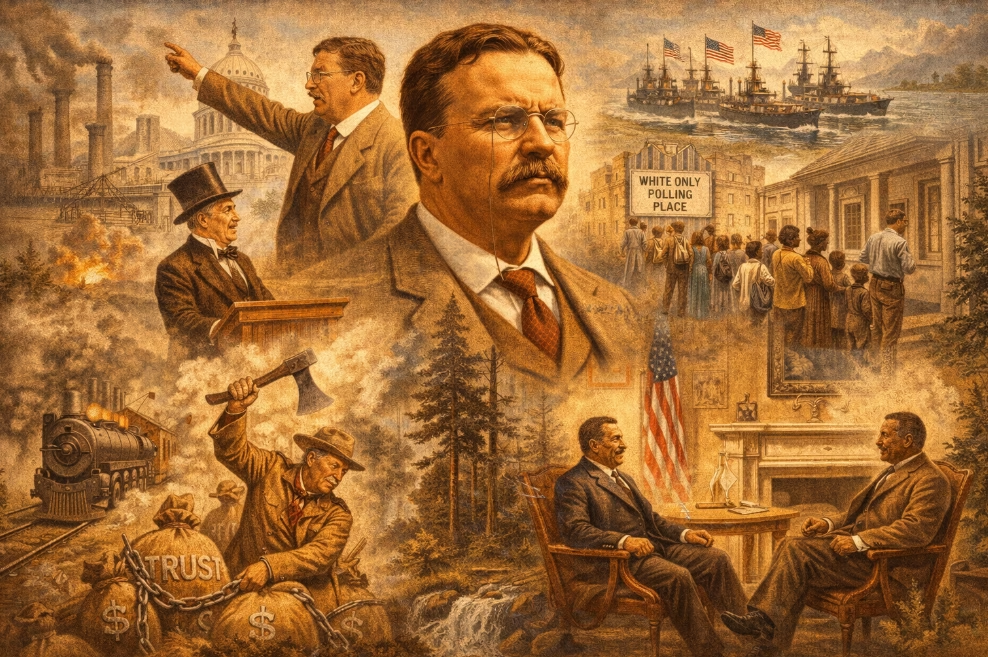

The Foundations of the American Century

By the time Roosevelt left office in 1909, the structure was in place:

- A modern navy

- A strategic canal

- Pacific footholds

- A doctrine of hemispheric oversight

- An assertive executive branch

- An industrial base capable of sustaining long wars

When World War I erupted, America had the infrastructure to intervene. When World War II demanded global mobilization, that industrial foundation, steel mills, shipyards, rail networks, proved decisive.

Roosevelt did not see the American Century fully unfold. But he helped engineer its starting conditions.

The rise of the American superpower was not inevitable. It was constructed through policy, conflict, negotiation, and debate.

And for Black Americans, that rise has always been layered. Pride in national strength exists alongside justified critique of domestic inequity. Military service, civil rights struggle, and global diplomacy often intersected in complex ways.

Power abroad. Justice at home. The tension continues.

Final Reflection

“Roosevelt’s Imperium” was not announced with trumpets. It emerged through patterns: naval deployments, economic strategy, presidential initiative, calculated mediation.

The republic grew comfortable operating on a global stage.

And once comfortable, it rarely stepped back.

The question Roosevelt’s era leaves us with is not simply how America rose. It’s how it chose to use its power and how it continues to reconcile its democratic ideals with its strategic ambitions.

That conversation, like the superpower itself, is still evolving.